Maryknoll Father Bill Donnelly reflects on the faith of the people of Guatemala who have endured years of violence and oppression yet live in hope that justice will prevail.

[P]recious in the sight of the LORD is the death of his faithful ones. - Psalm 116:15

Today, as we celebrate the feast of Corpus Christi, the readings give us an opportunity to reflect on sacrifice, specifically how Jesus sacrificed his own body and blood for our salvation. The images of sacrifice come alive for me as I reflect on these readings because as a newly ordained Catholic priest, assigned to work in Guatemala in 1965, I witnessed so much killing, bloodshed and sacrifice among the people I served for those first 24 years.

I was sent to a country experiencing a brutal civil war that officially lasted 36 years (1960-1996), although its roots were sown in the 1500s when the Spanish arrived in Guatemala. It was then that racism took root and set the tone for centuries of government-sponsored prejudice, oppression and injustice perpetrated against the Mayan indigenous majority. When the United States became involved by giving military aid to the Guatemalan government, this underlying issue of racism was overlooked. It was the fear that communism would spread through neighboring countries, and the coaxing of transnational corporations with business interests in Guatemala, that sealed the U.S.’s complicity. Despite the fact that the final peace accord was signed on December 29, 1996, unresolved racial tension, dynamics of inequality and violence continue today – now in the form of form of drug trafficking, gang activity, a criminalization of social protest, and extreme poverty, most apparent in the Mayan indigenous communities.

In the worst years of the war, between 1980 and 1990, I worked in a large parish, Santa Cruz, Barillas, in the northwestern department of Huehuetenango along with a Maryknoll brother, Luke Baldwin, and five Mexican and Guatemalan sisters of the Siervas del Sagrado Corazon y de los Pobres (Servants of the Sacred Heart and the Poor). We worked with lay catechists, and as a parish team we served the town of Barillas and the 55 mostly Mayan, K’anjobal-speaking, villages in the mountains and jungles surrounding the municipality.

Most weekdays, the parish team and I would travel by horse or walk for hours to visit the people in their isolated villages and celebrate Nass, baptisms and marriages. If it was safe to meet again at night, after Mass we would gather in the little adobe chapels and sing, tell jokes and discuss our faith. Since there was much propaganda against the Catholic Church, people had a lot of questions.

As the war worsened at least 1,000 people were killed in the villages of my parish, some assassinated by guerillas, most massacred by the Guatemalan army. The army targeted village leaders as suspected guerillas or guerilla supporters, and because the Catholic Church trained catechists as community leaders, all Catholics were suspect. Though the majority of the indigenous people wanted no part of the war, the Guatemalan military thought nothing of wiping out an entire village to eliminate one leader who they suspected gave support to the guerillas. As one catechist told me, “Padre, we are like sheep between two tigers.”

On this feast of Corpus Christi we celebrate the sacrament of Eucharist, given to us by Jesus on the night before his death. In the villages of Santa Cruz Barillas, the Mass and the Eucharist were key in bringing people together, but I could not visit all of the 55 villages frequently enough. Catechists and animators of the faith were trained and commissioned by the bishop to celebrate the Sunday and feast day liturgies, using the Blessed Sacrament reserved in their little village chapels for Communion.

Catechists had to travel many miles by bus, horse, and hiking to take the consecrated Hosts from the parish main churches back to their villages. The people loved having the sacramental presence of Jesus, especially in such sad, tense times. They deeply identified with Jesus; his death and suffering were not unlike the anguish they were experiencing. Knowing that Jesus conquered death and that he sacrificed himself to make their life in Christian community possible comforted them. In the midst of their pain and loss, they came to embrace the words of today’s Psalm: “[P]recious in the sight of the Lord is the death of his faithful ones.”

By the war’s end 250,000 people were killed and 50,000 disappeared; these ranks included priests, seminarians and sisters who were also martyred. Additionally, thousands of Guatemalans fled the country, many to Mexico where they lived as refugees. As the peace process got underway in 1994, the Catholic Church began a project of interviewing survivors and writing a history of what happened. The four-volume book produced, Guatemala: Nunca Mas (Guatemala: Never Again) was officially published and given to the Guatemalan people on April 28, 1998 in the metropolitan cathedral of Guatemala City.

Two days later, the long-suffering people of Guatemala received a strong message that their history of torment was to continue. On April 30, Bishop Juan Gerardi, the head of Guatemala City’s Archdiocesan Human Rights Office responsible for publishing the report, was assassinated. The next day the Guatemalan people defiantly marched to the capital for his wake and funeral. Together they sent a strong message to the powers of prejudice and violence that this death and their suffering recorded in the historical memory, like the brutal torture and death that Jesus endured, could not be the final word. They continue to live in hope that justice will prevail. The violence and bloodshed revealed in Guatemala: Nunca Mas was written as a testament that the people who survived it will never let it happen again.

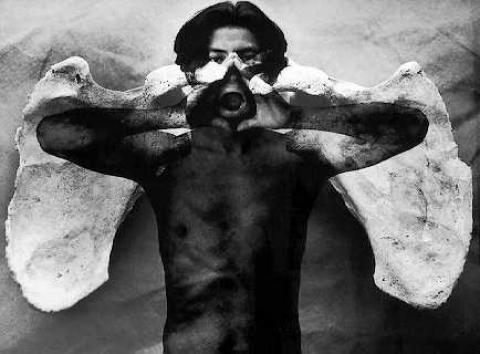

Photo: "Nunca Mas" (Never Again), the fourth in a series of angels created by Guatemalan artist and photographer Daniel Hernandez Salazar.