June 2017

Organized for change:

Solidarity Economy in Brazil, Part 2

Print and share the two-page PDF version

The solidarity economy movement in Brazil promotes innovative, democratic alternative economic structures based on collective ownership and horizontal management. The goals are to decentralize and root wealth in communities, and financially and politically empower participants toward a more just economy.

To achieve these goals, the solidarity economy is organized to value input from all sectors of society and to be open to change. With its unique organizing style, the movement has been able to influence government at all levels to support the solidarity economy.

Web of forums

The three main actors in Brazil’s solidarity economy movement—solidarity economy enterprises, support organizations, and policy makers—share information across an active web of forums that crisscross the 27 states, connecting local, state, and regional levels and traveling up to the national level and back again. This flow of information is the lifeblood of the movement.

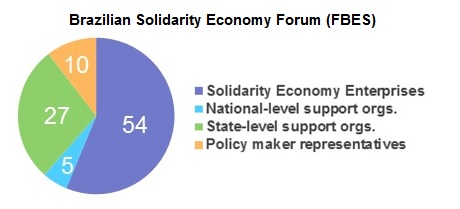

The national-level Brazilian Solidarity Economy Forum (FBES) is the most important decision-making entity. The 96 members of the FBES come from four sectors, the majority being solidarity economy enterprises (see chart below). They meet twice a year to organize, discuss, and prepare strategies for mobilizing the solidarity economy throughout the country.

The movement guarantees that representatives of solidarity economic enterprises are the majority of votes in all forums. This is to prevent voices from the grassroots being overtaken by support organizations or by policymakers.

Because public policy is essential to the advancement of the movement, members value the participation of government officials as active partners. Yet there has been debate over how best to include them since politicians have been known to try to use the movement for their own political gain. To avoid this, government officials and politicians can only participate in forums as members of organizations or networks representing them, such as the Brazilian Network of Solidarity Economy's Public Policymakers.

One example of how these actors interact is with recyclable material pickers, an important segment of Brazil’s solidarity economy movement. RECIFLAVELA, a solidarity economy enterprise, is a cooperative of recyclers in São Paulo assisted by Caritas Brazil, a support organization that provides technical assistance and by Caritas Australia, which provides funding. Both RECIFLAVELA and Caritas Brazil participate in the state-level solidarity economy forum.

For an interesting look at a recyclers' cooperative in the world's largest landfill, Jardim Gramacho outside of Rio de Janerio, see "Waste Land," a 2010 documentary directed by Lucy Walker. (http://www.wastelandmovie.com)

Cities and states pave the way for governmental support

Initially, during the 1990s, only a handful of city and state governments supported the fledgling movement. Cities with more progressive mayors and councils, such as Porto Alegre in the south, Belem in the north, Santo André in the southeast, and Recife in the northeast, created programs and incentives for solidarity economic enterprises.

Rio Grande do Sul was the first state to enact supportive policies and later served as a model for national implementation. These policies ranged from providing credit and technical assistance, establishing fairs and other venues to market the products and services of solidarity economy enterprises, leadership formation, and more.

Lula administration strengthens support for cooperatives

Federal support for the solidarity economy began with the election of Luis Inacio “Lula” da Silva as president of Brazil in 2002. With his long history as a union organizer, worker rights issues gained prominence during his presidency. “The solidarity economy,” he said, “is an alternative for generating jobs and income, besides being an important way to encourage the country to adopt sustainable habits as consumers that are just and in solidarity with workers.”

In his first year, at the request of the movement, Lula created two government bodies. First, Lula created the National Secretariat of Solidarity Economy (SENAES). He appointed Paul Singer, an Austrian-Brazilian economist and co-founder of the Workers Party, to lead the agency. Singer quickly became a key figure in the development of the solidarity economy in Brazil.

In 2014, Singer wrote in a ten-year retrospective that he focused the work of SENAES around an approach that he refers to as “endodevelopment,” and he defines as development that is “produced by the community that benefits from it.” In traditional development, investors and businesses from outside the community come to hire local workers. Only the few workers who are employed benefit. In endodevelopment, SENAES trains organizers to mobilize low-income communities to develop their own solidarity economy enterprises based on the backgrounds and interests of its members.

To help solidarity economy enterprises market their products and services, SENAES has established more and better venues as well as aided in the formation of “responsible consumption groups” that establish ties between enterprises and groups of buyers. Support organizations often partner with these and other governmental efforts to help solidarity economy enterprises.

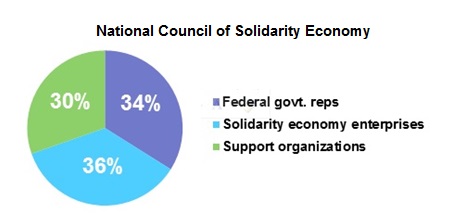

Lula also created the National Council of Solidarity Economy to include voices from the solidarity economy movement in the crafting of public policy at the federal level. The Council is composed of representatives from three sectors:

The results of these efforts at the federal level have been impressive. A 2011 study by sociologist Luiz Gaiger found that 22 of 37 national ministries had programs to support the solidarity economy. “If we include the five public financial institutions,” Gaiger wrote, “we have a total of 27 federal institutions with some kind of articulation in the construction of solidarity economy policies.”

Support grows slowly in Congress

In Congress, where agribusiness and corporations have dominant influence on votes, few members support the solidarity economy movement. Yet Congress has created two programs valuable to the growth of agricultural producers in the movement:

- Program for Food Acquisition from Family Agriculture buys agricultural products from family farmers organized in cooperatives to distribute to families in need;

- National School Feeding Program requires at least 30 percent of agricultural goods purchased by schools to be produced locally by family farms.

Recyclers organize for policy change

Recyclable material pickers have also achieved some important legislative advances. Since recyclers organized the National Movement of Recyclable Materials Pickers in 2001, Congress has slowly met many of their demands.

President Luis Inacio “Lula” da Silva (front row, center) with recyclable material pickers.

First, in 2002, Congress officially recognized their category of work, which provided recyclers the opportunity to pay into social security, among other benefits. The following year, Congress established an interdepartmental committee to encourage the creation of programs to benefit recyclers.

In 2006, Congress determined that recyclable materials produced by federal entities should go to recycler organizations, greatly increasing the amount of material available. The next year, Congress allowed city governments to form contracts with recycler cooperatives.

Finally, in 2010, Congress established the National Policy for Solid Residues, which set a deadline for the closure of all open air dumps by 2014. Though this goal has not been realized as of yet, the policy also requires municipal governments to include recycler organizations in their plans.

Recyclers in Brazil march with a sign that says “Come pickers, to the organized movement, since united we are strong and we will no longer be exploited!”

Current uncertainties

Unfortunately, the new administration of President Michel Temer is eliminating many of these advances. One of his first actions was to remove Paul Singer as director of SENAES. In our next edition, we will look at current threats to the solidarity economy movement and strategies the movement is pursing to grow into the future.