The following article was originally published in the December 2013 issue of El Quetzal, the newsletter of the Guatemala Human Rights Commission-USA. It was reprinted in the March-April 2014 NewsNotes.

Guatemala has endured conflict over mining for several decades, but over the last couple of years, the number and intensity of the conflicts have escalated.

Communities that oppose mining in Guatemala have been met with intimidation, cooptation, and even deadly violence. The violence is generally carried out by private security guards hired by the mining companies, but it is committed with the tacit approval of the government. The perpetrators all too often walk free, or, in cases when they are charged, are exonerated by Guatemala’s weak and corruptible judicial system.

Although the companies that mine Guatemala’s soil are domestic, they are universally contracted by, or subsidiaries of, foreign corporations. So, alongside ongoing local efforts to halt mining, affected communities and their allies have sought creative ways to hold the parent companies accountable abroad. Three struggles against mining over the last year have successfully brought their fight to mining companies in the U.S. and Canada: La Puya, San Rafael las Flores and El Estor.

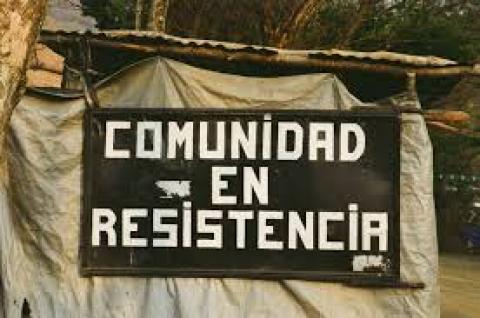

Since March of 2012, residents of the municipalities of San Jose del Golfo and San Pedro Ayampuc – just an hour outside Guatemala City – have blocked the road leading to a proposed mine. Residents set up a camp site and continue to take turns using their bodies to halt construction of the mine. This movement is often referred to as "La Puya."

The mining company, along with police, has tried to break through the roadblock various times, but each time they have been peacefully repelled. In addition, one leader, Yolanda Oquelí, was shot in June 2012 – a crime for which no one has been held accountable. There is a constant fear of another attack or violent eviction.

The project is owned by an American engineering firm, Kappes, Cassiday and Associates (KCA), so members of La Puya looked to cross-border organization to bring the fight to the U.S. Yolanda, as well as fellow activists Tono Catalan and Alvaro Sandoval, has spoken to U.S. audiences in Washington, D.C. and Ft. Benning, GA, mobilizing them to contact KCA as well as the U.S. government to demand that the rights of protesters be respected.

Then, in June [2013], Alvaro traveled to Reno, Nevada where KCA has its headquarters. Alvaro joined local anti-mining activists to stand up for the rights of communities in both the U.S. and Guatemala to have a say in what happens to their local environment. Americans have made it clear that if activists at La Puya are injured or arrested, KCA could be partially liable.

A common tactic used during the Perez Molina administration has been to provoke violence, or directly carry out attacks, claiming there is evidence of organized crime, and then use that as justification to respond with heavy military repression. Over the last several months in San Rafael las Flores, where residents are opposed to a silver mine, there have been multiple violent incidents. Poor investigations carried out by the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the outright manipulation of evidence by police make clarification of the facts unlikely. Nevertheless, the government has blamed groups protesting the El Escobal Silver Mine. (The protesters have denied the accusations.)

What is clear, however, is that some attacks were perpetrated by the Canadian mining company, Tahoe Resources, and its private security firm. On April 27, [2013,] a group of local residents left a protest camp along the road that passes directly in front of the mine. When they passed the front gate, security guards opened fire on them from the other side. The head of mine security, Alberto Rotonda, was caught on tape ordering their execution. Though Rotonda was arrested, he was only placed under house arrest, and his trial has been interminably delayed.

At the beginning of June, Canadian groups lodged a complaint with the Ontario Securities Commission asking them to investigate Tahoe Resources for the shooting. The complaint alleges that Tahoe’s disclosure about the attack was insufficient and inaccurate. Tahoe’s shares dropped after the complaint was filed, down to about $12 a share in July after reaching a high earlier in 2013 of nearly $19 per share. The price has since rebounded, and on October 13 the company made its first shipment of silver concentrate. Still, the market’s reaction to the complaint demonstrates that Canadian mining companies who perpetrate violence can be hit where it hurts: their profits.

Victims of violence at the hands of a private security firm hired by HudBay Minerals have also taken their fight for justice to Canadian soil; however, in this case they are using the Canadian courts.

In 2007, as part of ongoing conflict over a nickel mine in El Estor, Izabal, 11 women were gang raped during a mass eviction. Then, in 2009, a schoolteacher was killed and a young man was paralyzed – all allegedly by private security personnel hired by a subsidiary of HudBay Minerals. (The women report that they were also raped by police and soldiers).

HudBay Minerals has argued that it can’t be held accountable for abuses committed by a subsidiary. However, the plaintiffs claim that HudBay made decisions on the ground for its subsidiary. They also claim that HudBay was negligent in hiring unlicensed, untrained security guards in a country overrun with violence and ruled by impunity.

In July [2013], the Ontario Superior Court ruled that the case can be heard in Canada. This opens the door for other, similar cases – where subsidiaries of Canadian companies commit abuses outside of Canada – to be tried in Canadian courts.

The ruling established that the plaintiffs will have to show that either HudBay minerals had direct and complete control over its subsidiary, Compañía Guatemalteca de Niquel (CGN), or that it was negligent in not preventing the violence caused by CGN. Part of the plaintiff’s claim of negligence is based on Guatemala’s high murder rates, especially of indigenous leaders, and Guatemala’s high rate of impunity. Thus, this case will put Guatemala’s government itself on trial. The plaintiffs argue that Guatemala is so violent that a mining company that ordered the eviction of indigenous communities should have known that human rights abuses would be committed.

The last few years have shown us that any company that mines in Guatemala where there is community resistance could be considered negligent. With evidence of systematic violence and heavy-handed repression against anti-mining movements, one could argue that human rights violations are to be expected. Similarly, impunity for attacks against anti-mining groups is so widespread that victims have no chance of finding justice in the country.

Whether the case of gold mining at La Puya, silver mining in San Rafael, or nickel mining in El Estor, years of sustained community resistance show no signs of relenting. Meanwhile, transnational mining companies that benefit from government corruption and entrenched impunity, disregarding basic human rights obligations to increase profits, should perhaps not be so confident they will get away with it.

Photo of sign from La Puya from the Guatemala Solidarity Network/UK